Resident Evil is a video game series that remains praised to this day. One that is considered to have forever changed the landscape of gaming history. It’s a series that took many risks, and despite all of them being horror games, spanned many different types of different gameplay mechanics to keep things fresh. There are seven adaptations so far, with the eighth one being a reboot directed by Zach Cregger. However, the first six (except parts two & three) were directed by Paul W.S. Anderson, a director who is not exactly praised, despite him taking risks with most films. Resident Evil: Retribution is the entry that has taken the most risks thus far.

The British Film Institute (BFI) listed this film as one of the ten great sci-fi horror films, stating that this film “[drops] any pretense of narrative cohesion for a balls-to-the-wall symphony of movement and abstraction.” One with a “thematic engagement with the form.”1 Slant Magazine gave this a 3.5/4, stating that Anderson only upholds the values of “endless pleasure through endless bone-crunching mayhem, balletic ass-kicking, abstract visual design, and photographing his wife and muse, the always extraordinary Milla Jovovich.”2 However, this was disliked by both mainstream critics and movie-goers. A 28% score on Rotten Tomatoes, a 5.3/10 on imdb, a 2.5/5 on letterboxd, and icheckmovies having a 89:307 favourites to dislikes ratio. In fact, when posting about this in the truefilm subreddit, it quickly got removed.

Because of its reception, this is not your standard opinion, but I believe that this film, Resident Evil: Retribution, is a rare case of what video game adaptations sought out to do and is the antithesis of modern gaming culture. It is a film that not only succeeds in the surface level structure for the game, but also the mechanics and philosophical aspects of one. It is one that prioritizes the video game code, the visceral form of how a video game works, as opposed to the content of a modern cinematic game.

The Adaptation of Two Mediums

Near the time of the film’s release, video games were reaching for photo-realism but weren’t at the point of creating the “cinematic game”. While there were titles such as Uncharted trilogy, they were more based on a pattern consisting of a scene, climbing/puzzles, then an action sequence. The pure cinematic game, based on long and frequent cutscenes, didn’t start until The Last of Us. While the Metal Gear Solid series is an obvious exception, Hideo Kojima was an auteur going for his specific vision, and not an industry trend. Similarly, the earlier point and click adventures games were Full Motion Video (FMV), which blurred the line between a video game and your standard live action film to the point that gameplay could be completely non-existent.

Otherwise, the games were defined by the form of their gameplay. The smooth controls of a platformer, the social interaction of multiple titles such as Halo, Goldeneye, or EA Sports games, and the claustrophobic complexity of Doom levels. These were all meant to give a more visceral reaction. In terms of being a video game, it became a detriment to have one based on long and frequent cutscenes. In the end, the cinematic game is a style that aims for the same effect as a blockbuster film. A film that focuses on content. Video games before that, especially because of the lack of hardware capabilities, didn’t have the means to do so. Therefore, it focused on the gameplay, which resulted in dealing with the form. How did the gameplay viscerally affect you?

Video game adaptations weren’t a new concept before the start of cinematic games. However, they all tried to translate it from the form of the game, the visceral experience, into a content-based film. Basically, the films felt like long and unnecessary cutscenes. They were today’s cinematic games. They were even considered failures. Not only by the rapid and hostile fandoms, but by the critics that were unaware of the previous media. While I personally enjoyed several of these films (Super Mario Bros., Mortal Kombat, Lara Croft: Tomb Raider, and DOA: Dead or Alive), I did so by viewing them as standalone films, divorcing them from the source material.

It was with Resident Evil: Retribution that everything changed. It does not focus on a narrative, or even character development. Its sole goal was to adopt the form and structure of a video game. It wasn’t received well for those aspects, but this is precisely what makes this the one true video game adaptation.

It’s Like a Camera – Just Point and Shoot

Some background information is needed for this film. It is one where seeing the other entries are needed, but not for Marvel-style fanservice. Rather, it shows how the characters from other films can be treated as non-playable characters (NPCs), the “extras” of the video game world, and how their identities fit into that. There are also the callbacks to earlier scenes that show they are levels, not standard cinematic scenes.

The film begins with a continuation of the end of Resident Evil: Afterlife. In fact, it is shown twice, like it is an unskippable opening cutscene. Afterwards, there is a two to three-minute summary of the entire series up to this point, establishing the lore of the universe like it’s a game manual or an opening scene of an older game. It doesn’t waste time with the cinematic method – it jumps straight into the “mechanics”.

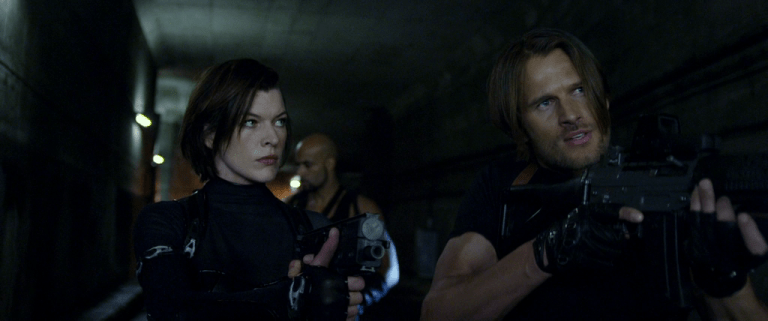

The basis is then needed for the current entry. The protagonist Alice, is naked and subjected to interrogation. She is then released for no reason and given an armoured outfit. At this point, she finally has control, giving the feeling that the cutscenes are over and the player now controls the environment. This is helped emphasized by the armour. As she has control, she has access to her inventory and can wear the outfit. Shortly after she is in a safe hub, given weapons, and is then given the mission briefing: the only scene dedicated to the narrative of the film. Here’s the goal, here’s the stakes, now play the game. Everything that follows is pure, stylized, over-the-top action, showing that it then turns into a video game that focuses purely on gameplay.

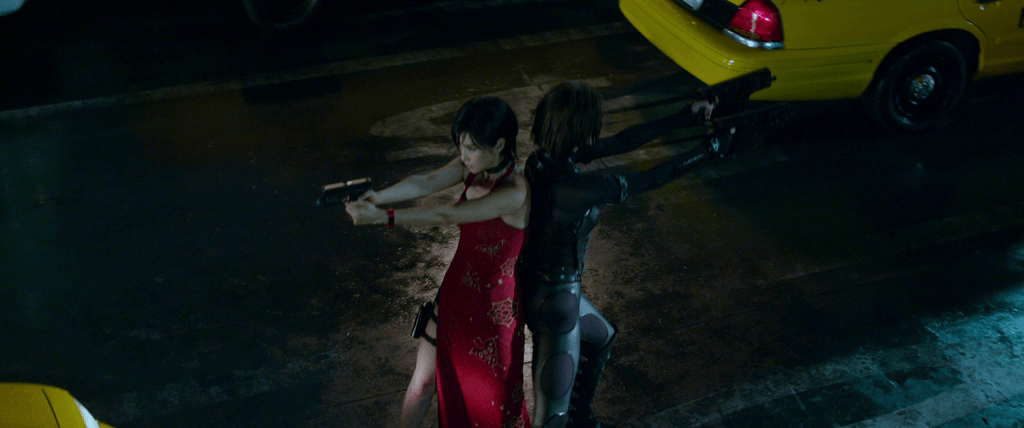

The structure of the film’s world is the most overt way of showing its video game environment. She runs through a hallway when she is released from the interrogation room and is suddenly transported to the same Japanese setting as in the opening scene in Afterlife. In fact, some of the exact same shots as in that entry were used. However, now Alice is involved. She smashes a cop car window for a gun and finds a chain, and what may be considered an NPC, a cop, changes his pathway to look at what happened to his car. The zombie outbreak that inevitably happens is completely different thanks to her changes. There then is another hallway and the realization kicks in: this is a simulation. A contained environment. In video game terms, it’s a hub, or a level.

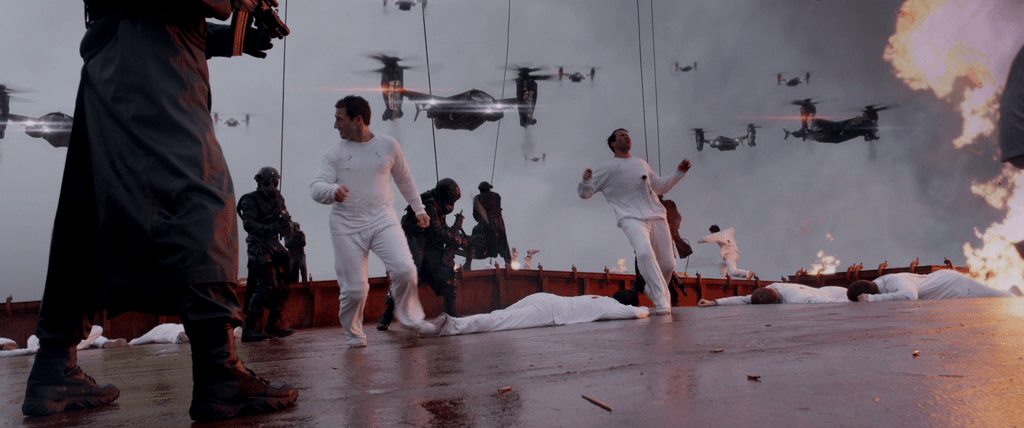

The hallways are separated between said levels and could be seen as the loading/map screen. They are like the castles that Mario enters in every level in a Mario game, or the commonly used save-point. The levels then follow into the usual gameplay mechanics, featuring waves of enemies that become stronger over time, complete with new weapons or vehicles. It even culminates into full-scale boss battles.

The Video Game Philosophy

The true genius of the film lies in the philosophical use of how NPCs and playable characters operate in a game. The book Exploring Videogames with Deleuze and Guttari summarizes that what separates video games from other artistic mediums is that while the developer is the artist, the player becomes the primary artist as the “artistic piece” changes in a fluid way depending on how the player interacts with the game.3 Retribution shows this perfectly.

There is a scene in the film of an assembly line. All the characters in the series are there, carried through the line as a blank slate. They don’t have a facial expression, no interactivity. They are a hollow empty shell being taken over to whichever hub a specific one is assigned to. This falls under Deleuze and Guttari’s concept of the body without organs, which is the shift in one’s identity, or the fluid, unassigned state of a character before the specific forces act upon them. Showing them as a blank slate is the most overt way of doing so. An early scene showing this is an NPC Alice – who instead of being the protagonist we usually see, is now a housewife, complete with a different hairstyle. She lacks the combat finesse and quickly dies in the suburbia level she is assigned to. This shows how her identity was based on affects, which is what changes her with the use of external forces.

As Colin stated, an example with how this works for video games is with a game like Grand Theft Auto III. Many of the NPCs look alike as if they are clones, but their identities are all different in the end. One may have been run over by you, one may have run away after witnessing gunfire, and one may never interact with you. The soldiers from the first Resident Evil film are assigned identities as well. One of a soldier’s blank slate was used as both said soldier, and a surviving neighbour in the suburbia level, showing how one “preset” can represent two different NPCs.

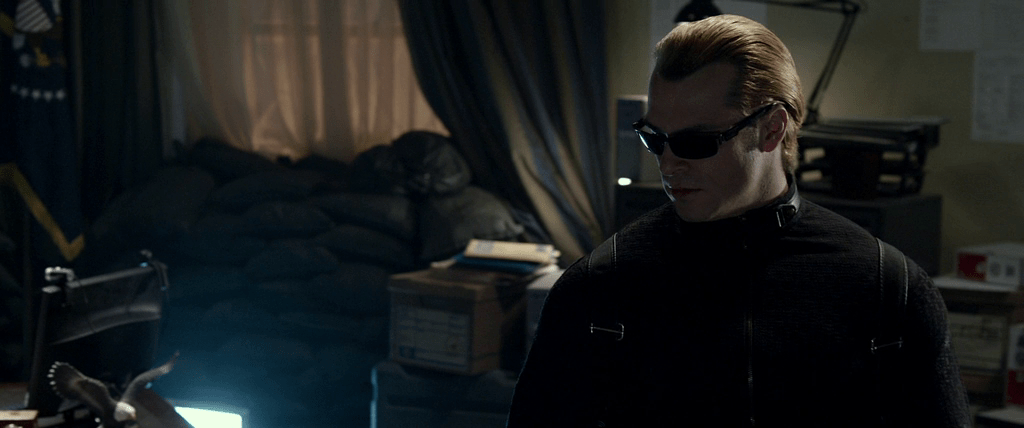

The protagonist Alice is the outsider, showing that she’s the playable character as she is entering the base of the simulations. This can be seen as her entering the system, the video game itself. This also includes the other characters that come in from the submarine portion of the base, outside of the levels. These are people that partake in separate levels before joining in with Alice. This is best shown by Jill Valentine, who initially appeared in the second film. This time, she is under a mind-controlling device by the Umbrella Corporation. The shift in her identity is not only made visible through the changes in her character, but also through her acting style. It is unnatural and frankly sounds awful; but that is the point. It is now stylized to show that shift in her identity, thanks to the effect of the mind-controlling device, the external force that shifts it.

A final, amusing touch of its experience is how Alice explains to someone how to use a gun to the simplest and most interactive form. She gives one simple instruction: “It’s like a camera – Just point and shoot.” Doesn’t that perfectly encapsulate the video game experience?

Sources Used:

- https://web.archive.org/web/20200820025719/https://www.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/news-bfi/lists/10-great-sci-fi-horror-films

- https://www.slantmagazine.com/film/resident-evil-retribution/

- Exploring Videogames with Deleuze and Guttari – Colin Cremin

Leave a comment